Muslin: Gossamer of the East

Muslin: Gossamer of the East

“The fineness of the cloths is difficult to describe, the skin of the moon removed by the executioner-star would not be so fine. One would compare it with a drop of water if that drop fell against nature, from the fount of the sun… it is so transparent and light that it looks as if one is in no dress at all but has only smeared the body with pure water.”

-Abul Hasan Yaminud Din Khusrow; Indian sufi poet and scholar describing Muslin.

History of Muslin :

Muslin was the attire of kings, the adornment of queens, and a fabled fabric which was the pinnacle of fashion. Rare, delicate and fine, described as “woven air”; Muslin was the most sought after material. Fact, fictions and myth merged into one, as the stories of this coveted textile traveled the earth, bringing prosperity to its traders. From Rome to Indonesia, the cloth that had started as courtly gift became a symbol of exclusivity, empowerment and taste that occupied a central position in European enterprise, with Bengal at its nucleus.

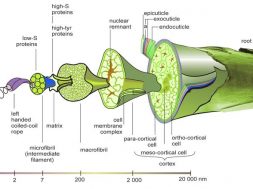

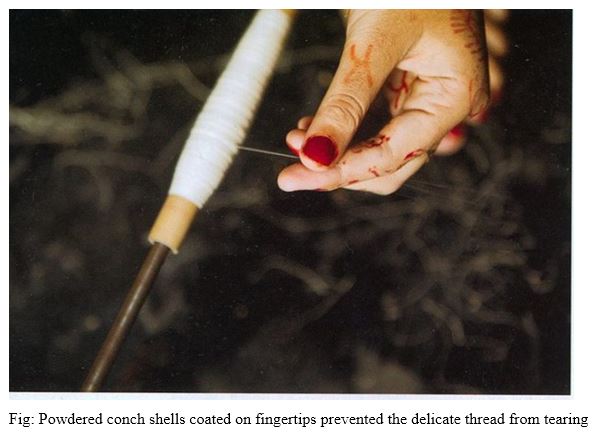

Muslin was the pride product of Bengal, specifically of the part known as Bangladesh today. The unusual environmental characteristics of a short stretch along the Meghna river provided the precise conditions for a particular variety of the cotton plant and the industry to flourish. At the same time, communities of skilled people took on the painful process of saving seeds and planting them, harvesting cotton, spinning yarn and weaving cloth. Manufacture of the best Muslin involved a well-choreographed sequence relying on each craftsperson performing his/her role, drawing on inherited knowledge and innate ability. It transformed cotton into the legendary “Gossamer of the East”, which fires our imagination to this day. Dr. Taylor, a British textile expert states in a report, “Hindu women at the age varying from 18 to 30 years, were the weavers of superfine quality. But after 30 years, their sight became impaired. The superfine quality could be woven only in early morning or afternoon as otherwise the strong sunlight snapped the thread.” Despite numerous efforts, the plant grew nowhere else.

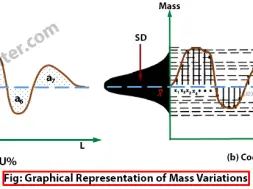

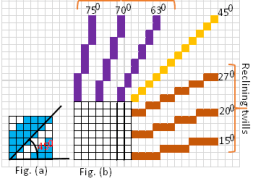

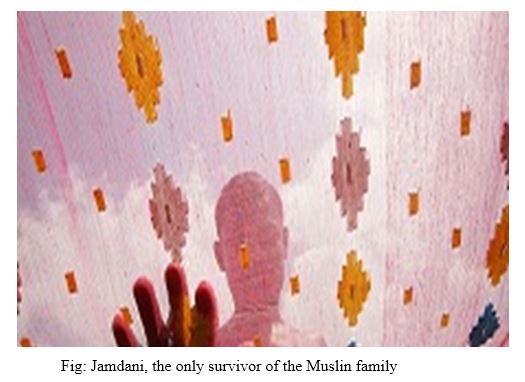

Jamdani, mainly of Bangladeshi origin, is the only one of the many variants of Muslin (called “mulmul”originally) which still survives. Sadly, today Muslin is all but a remnant of history. Bangladesh’s museums are empty of its finest specimens, the spinners who created the almost invisible threads of cotton have been displaced and the weavers who created this coveted cloth have ceased to reach for such rarefied heights of “counts” (this denotes the numbers of threads per square inch, the higher the number, the finer the cloth) that went beyond the double figures one sees today up to 1000. At that time myths and stories used to swirl around it. A cloth so fine those 6 yards of cloths effortlessly passed through a ring, so sheer that it would blend with the morning dew, so fine that mermaids were thought to have made it on misty mornings.

“Muslin” was named by Marco Polo after the large cotton trade through the town of Mosul in Iraq, supplied from Masulipatnam; Muslin was previously addressed as “fine Gangetic cotton from Bengal”. Its unique lusture and extreme demand attracted nobility and merchants. The East India Company who in 1765 earned the sole trading rights to Bengal from a derelict Moghul king, Shah Alam, exiled from Delhi. From a customer portfolio of over twenty markets, the English applied monopoly rights and extortionist laws which made its manufacture untenable for the defenceless craftspeople of the land. Ravaged by famines, eroded by overseas imitation, hounded by debtors, its Coup De Grâce was the Western technology that rapidly converted Bengal from a bountiful producer of handmade fabric into the supine recipient of industrial textiles. It also brought unimaginable wealth to the East India Company, and rose to account for half of the company’s world trade.

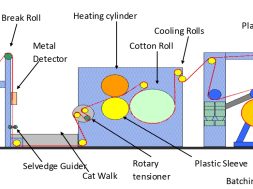

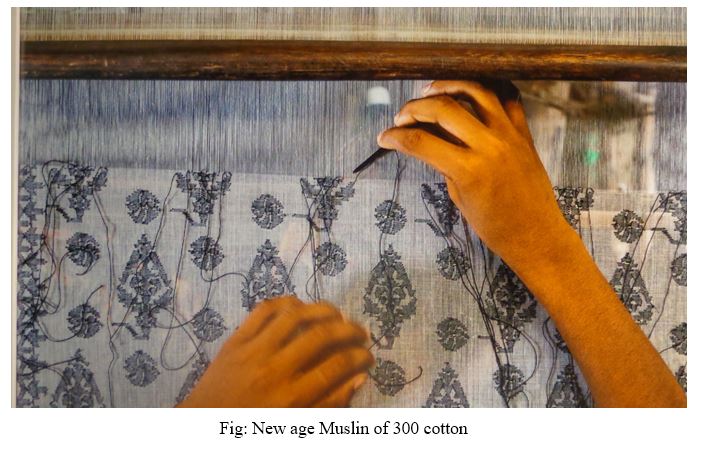

It is a matter of hope that some creative organizations are trying to recover the essence of Muslin and under their guidance and patronage, a group of weavers have become successful in weaving saree that has a thread count of 300 per inch showing all the traits of Muslin. Not only that expert’s journey have been started on the banks of the river Meghna, from Kapasia (named after the cotton plant) until Mymensingh in search of the remnants of cotton plant. Modern methods of humidity control and static measurement are being introduced to assist the weavers in overcoming problems of yarn tear and breakage.

how close they can now get to the original fabric.

All these efforts are going on to reveal the story of Muslin, the fabled fabric of Bengal and to inspire the revival of a new-age Muslin. It is expected that if Bangladesh can re-establish itself as the original source of this diaphanous material, it will be of tangible benefit to our handloom industry and also to our national identity. Our country, presently defined in textile within the narrow boundaries of a readymade garment industry with its accompanying controversies, can redefine its profile as also a provider of the finest textile, bringing pride and recognition to its true heroes- the craftspeople of Bangladesh.

(188)